Don’t Start With A Bang

People often think stories are supposed to open with a bang, with excitement, something that’ll grip the reader by the throat.

But not all stories are bang-y; or exciting; or go for the throat.

Often what you really want is simply this: to tell the reader what kind of story this is.

That’s enough for the right readers to decide to dive right in.

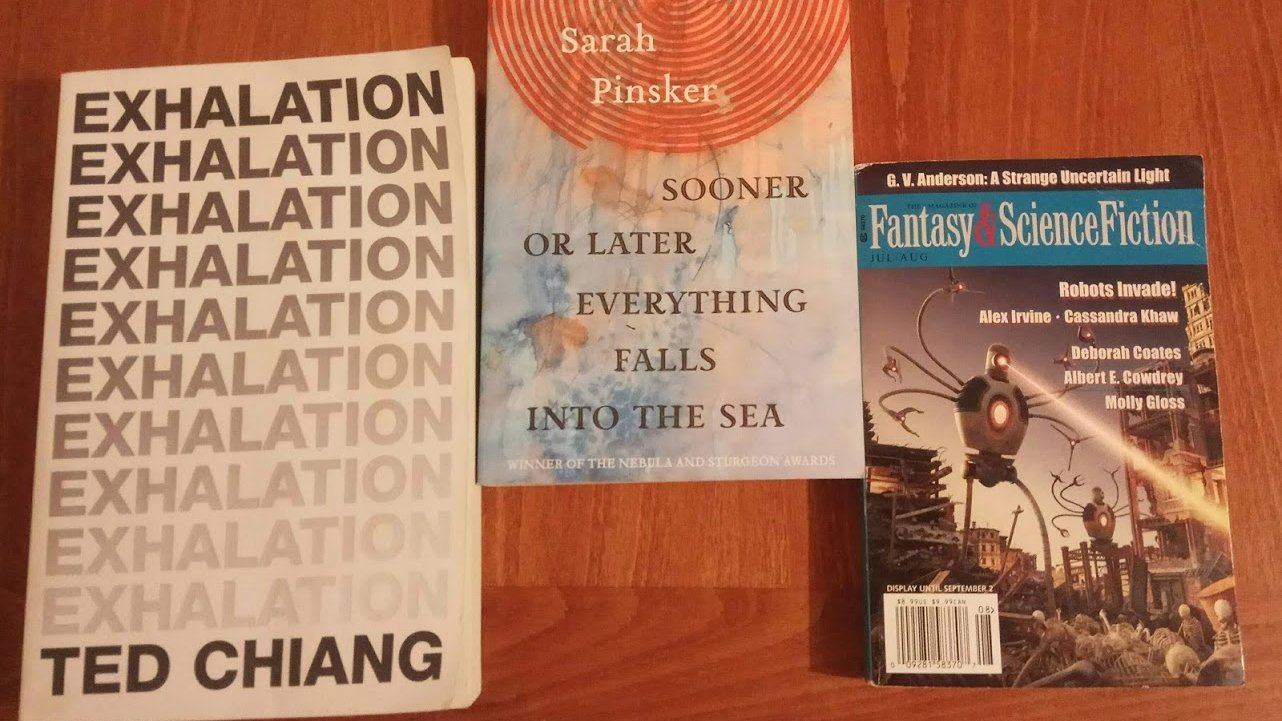

Some observations on openings -- originally written in 2019, courtesy of my first slushreading stint at Diabolical Plots , plus the very excellent collections I was reading at the time.

Consider, if you will, these three story openings.

"The Merchant and the Alchemist's Gate,” by Ted Chiang:

"O Mighty Caliph and commander of the faithful, I am humbled to be in the splendor of your presence; a man can hope for no greater blessing as long as he lives. The story I have to tell is truly a strange one, and were the entirety to be tattooed at the corner of one's eye, the marvel of its presentation would not exceed that of the events recounted, for it is a warning to those who would be warned and a lesson to those who would learn."

"Wind Will Rove," by Sarah Pinsker:

"There's a story about my Grandmother Windy, one I never asked her to confirm or deny, in which she took her fiddle on a spacewalk. There are a lot of stories about her. Fewer of my parents' generation, fewer still of my own, though we're in our fifties now; old enough that if there were stories to tell the would probably have been told."

"A Strange Uncertain Light," by G.V. Anderson:

"Anne twirled the thin, dull wedding band around her finger, quite loose. In their rush to be married, they'd failed to have it fitted properly."

These are three fantastic opening lines. But notice that none of them, by any stretch, is a "start off with a bang" opening.

Nothing's happened—yet.

What is it that they *do* accomplish, then?

In film, you'd generally open with an establishing shot. In a story, it's not entirely dissimilar—the question is, what is it that's being established?

It’s not necessarily a place. It’s not necessarily a scene. The three examples we’re looking at here don’t spend a word, yet, on where we are or what’s happening (although each one has its hints). Let’s see what they each do establish:

"Alchemist's Gate" establishes a straight-up promise: "The story I have to tell is truly a strange one."

This is going to be WEIRD. You are going to be AMAZED. Hey, here's a strange thing I made up -- this is going to be STRANGER THAN THAT."Wind Will Rove" does something entirely different: a whirlwind tour of the story's key elements.

This story has spacewalks, and fiddles, and quirky grandmothers. And, a melancholy insinuation that every generation is just getting duller."A Strange Uncertain Light" packs a whole relationship into a pointed symbol: the marriage is so rushed; will it fit?

I want to repeat: Nothing's happened yet. Characters haven't been introduced. We don't know the situation. Absolutely zero plot has occurred.

Nothing's happened yet.

What has happened is simply this: We, the reader, have been told what kind of story we're reading.

THIS story is going to make you feel amazed.

THIS story will be about strangeness and uncertainty.

THIS one will be "oh wow, my grandmother was WAY more awesome than me."

And here’s what was really interesting to me as a slushreader: A lot of submissions? Didn't really have that.

I'm not talking about did they manage to accomplish it really well, condensing the core strengths of the story beautifully and compellingly into a punch of an opening paragraph.

I mean, 500 words into the story, I still wasn't clear on what kind of story it was meant to be.

Things were happening, but that didn't mean I knew why they were interesting. Or things weren't happening -- probably in order to build up detail, for later, when things would happen.

Now, the Diabolical Plots submission system does something I found remarkably helpful and eye-opening on this: It puts a mark in, at precisely 500 words.

Like so:

==500==

When you next read a story -- try pausing for a moment at about 500 words.

It's not very much. But also, not so little.

At 500 words -- what do I know about this story I'm reading?

Usually, you won't know the plot. It's only just started.

You'll have a sense -- but not much more -- of characters, setting, voice, stakes.

That sense, though, is your map and guide to the story.

It literally tells you what in the story is important. And feeling that something in the story is important—well, that's what makes it a story, right?

That's why my point here is: Wanting the first line of the story to “grab me by the throat” is a high bar.

And for a lot of stories, that kind of intensity isn't even what I want.

Instead, what's important is the signal.

“Here's what you're in for.” “Here's where you should be looking.” “This, right here, is going to be the important bit.”

You’ll notice this places a certain requirement on the story: It needs to have an important bit. It needs to have answers for “what am I getting out of this,” or “what am I looking for here.”

And that'll be hard or impossible if your story is mostly "well, this is what happens next," even if the individual elements are individually great.

That's what makes openings so interesting to me:

They need to get across why the story is interesting, what it's about, what it is,

they need to do that BEFORE the story has played out and gotten there.

By the same token, if the opening doesn’t give me any hints about why the story is interesting, or what its heart is, that's often a signal that it hasn't cohered around anything in particular. (Or, of course: It's simply cohered around something that I personally don't connect with! That certainly happens too.)

At any rate, the experience has given me some new things to think about, and a new side of the craft to appreciate.

And hey, if it’ll help,

I’m happy to scribble some helpful "==500==" marks in any books you've got handy.